On this page we will be sharing current projects and collaborations. Focussing on different aspects of Laenen’s work and legacy.

The deconstruction of Studio II, a collaboration with Philip Angermaier, Niko Dockx, Rien Schellemans, Jackson Shallcross-Platt, Jeannette Slütter, Ersi Varveri, Gijs Waterschoot, and Yi Zhang.

![]()

© Ersi Varveri/ Pink House Press

© Ersi Varveri/ Pink House Press

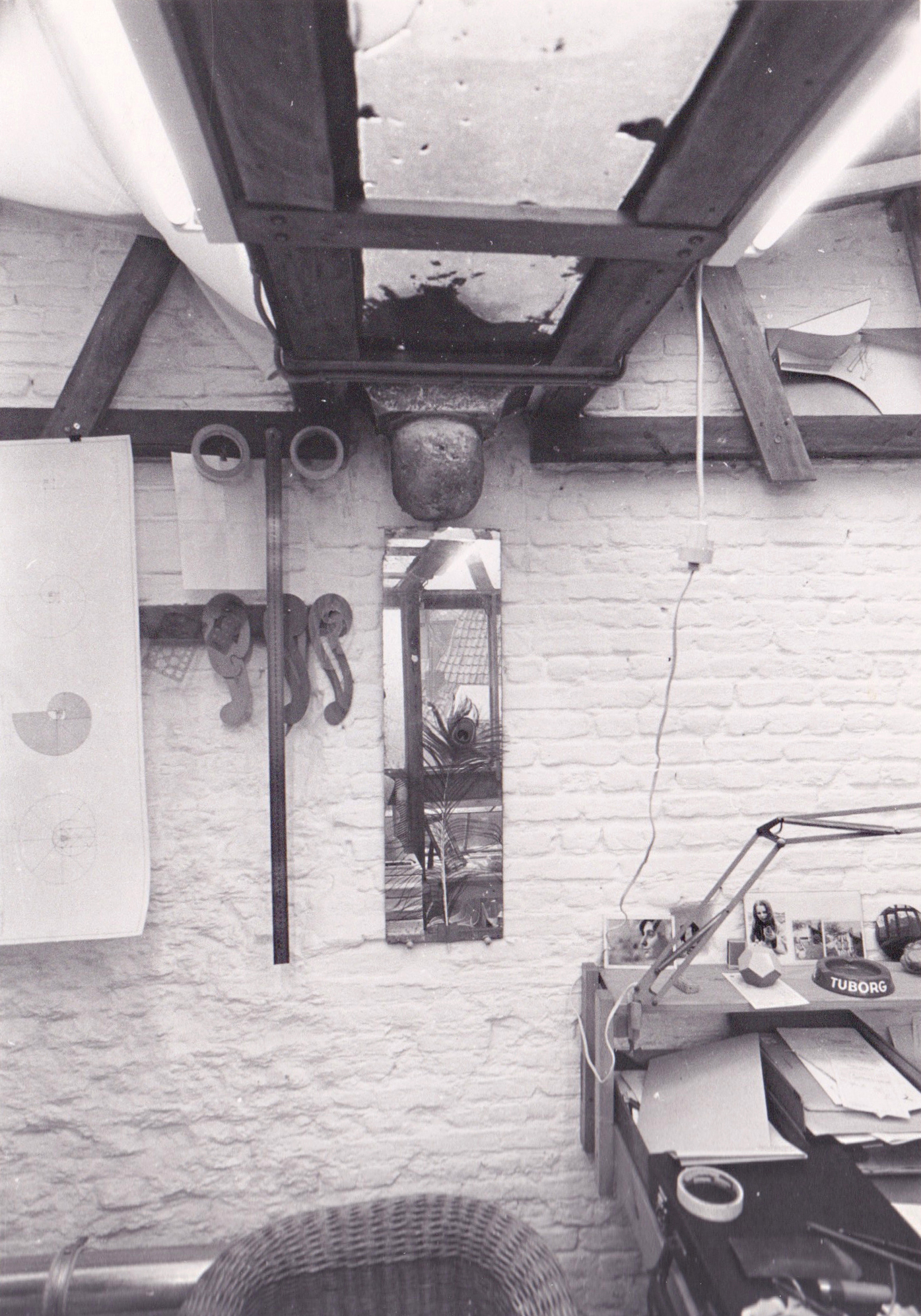

What started as a series of conversations with Nico Dockx and Judith Wielander (Expanding Academy), quickly turned into a one-week workshop, which took place in October 2021 and was centred around the ‘deconstruction’ of Laenen’s former studio in Mechelen. Conceived as a light-weight structure leaning against the historical city walls surrounding the garden and courtyard, this two-storey studio space overlooking the roofs of the old beguinage of Mechelen was built and designed by Laenen in the 70s. He later moved his studio to the garage located at the other end of the garden.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Images: © Jean-Paul Laenen Estate

Unfortunately the condition of this construction - which, together with the renovation of the house, was put forward by Jef Cornelis as an example of a new movement in, and ‘new hope’ for, architecture in Belgium in his documentary EEN EEUW ARCHITECTUUR IN BELGIE 1875 - 1975 (A Century of Architecture in Belgium 1875 - 1975) in 1976 - had deteriorated substantially over the years, forcing us to take action.

With Nico Dockx we conceived a one-week workshop that would serve as a testcase, an opportunity to dissect and study the construction by dismantling it. What followed was a week of intense labour, deconstruction on steroids, equally franctic documenting, continuous cooking, shared meals, stimulating exchanges, the occasional fire-making session, early mornings, and late night conversations - step one in what we hope can be a series of workshops, reconstructing and rethinking the temporary structure in the particular context of this site.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Images: © Jean-Paul Laenen Estate

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Images: © Jean-Paul Laenen Estate, © Ersi Varveri/ Pink House Press (black & white)

Images: © Jean-Paul Laenen Estate

Unfortunately the condition of this construction - which, together with the renovation of the house, was put forward by Jef Cornelis as an example of a new movement in, and ‘new hope’ for, architecture in Belgium in his documentary EEN EEUW ARCHITECTUUR IN BELGIE 1875 - 1975 (A Century of Architecture in Belgium 1875 - 1975) in 1976 - had deteriorated substantially over the years, forcing us to take action.

With Nico Dockx we conceived a one-week workshop that would serve as a testcase, an opportunity to dissect and study the construction by dismantling it. What followed was a week of intense labour, deconstruction on steroids, equally franctic documenting, continuous cooking, shared meals, stimulating exchanges, the occasional fire-making session, early mornings, and late night conversations - step one in what we hope can be a series of workshops, reconstructing and rethinking the temporary structure in the particular context of this site.

Images: © Jean-Paul Laenen Estate

Images: © Jean-Paul Laenen Estate, © Ersi Varveri/ Pink House Press (black & white)

Jean-Paul Laenen (Mechelen, 19 June 1931–14 April 2012) was a Belgian artist. He was predominantly known for his many sculptural works (among them, Ariadne’s Thread in the European Quarter in Brussels), as the designer of the penultimate Belgian five-franc coin and as a founding member of the multidisciplinary (architectural) workgroup KROKUS with architect bOb van Reeth and urban planner Marcel Smets, a group that focused on the rehabilitation of neglected neighbourhoods, most notably the historical city centre of Mechelen. Laenen lived and worked in Mechelen all his life. His house and studio are located on a site that historically served as a bleaching field for one of the city’s old beguinages. Laenen was introduced to the site by his father, a Volvo dealer that saw the then wasteland as an ideal location for the construction of a new garage. A house lay vacant on the plot. It had an inner courtyard and several small annexes. Leanen proposed to temporarily occupy these and, over the years, as his father fruitlessly tried to obtain a building permit, Laenen slowly transformed it into his home and cultivated the wasteland, turning it into a flourishing green garden. Mechelen was his everyday sanctuary. In the 1980s he had the opportunity to buy a ruin in the South of France, an area he had fallen deeply in love with twenty years earlier and where he went on to build his second home and studio. During the next decades, he would divide his time between Mechelen and Provence.

After Laenen died, his daughter and granddaughter managed his estate. They are currently engaged in the protection of the cultural heritage he left behind in Mechelen (and Provence), making it the place it is today. One aspect of the heritage are the works he left behind, the other is the private world behind them. For visitors and aspiring artists alike, it is a unique experience to encounter a place that opens up the artist’s inner world as it does in Mechelen. You are invited into his deep love for place and to see how it not only was present in his art, but also merged with his life through his garden and house. Like the acquired sculptural details he scattered about the garden, the large wooden sculpture by the bathroom or the creature in black mosaic executed directly on the living room wall. The following story is based on many nights in Mechelen coloured by Provence, in cause and effect by friendship, art and quarantine.

‘What he meant to say is not there, for he understood something else, something that was all-embracing, and he could not say it in words but only by living as he did.’1

Casts and cars

Early summer wipes the perspiring forehead of a casino, an awkward body towering on the outskirts of the city, on the fringe of branded nostalgia and Big Macs. We observe its striving outlook from a frituur across the street before we turn our backs on it and run our fingers by a lazy hinged steel gate whose fence has been swallowed by wild growing ivy and hops. Generations pass the ebb and flow of the deep-fried air as we open the gate and reach the entrance five steps in. Number 43, a light-blue faintly chipped wooden door in a car garage. Inquisitive pink roses guard the threshold and nip at our hair as we lean in to knock. They clearly question our intentions but let go as the door opens and we are greeted inside. Our host steps back, we step in and behold the scene that plays out inside as the years fall into place.

The space is engulfed in sun that streams past a tall hedge of rampant lush bamboo waving at us from the windows in the back. The narrow strips of light glide through the leaves, pass the glass as if one and the same, bounce off the walls and embrace the space in a soft yellow, primula kind of light. The old garage appears weightless in this state, perforated by rays that swallow the continuous sound of passing cars as we close the door. It’s been a long time. – Decades, nods the mechanic. He grabs a wrench from the wall in the adjacent room and enters the pit through a trapdoor. The garage eventually moved on to a man that years later leaned back in a large armchair as an artist and gave shape to the white sheet added a decade later by his daughter. She plugged in the radio when he left and scrubbed the walls in the company of her daughter. Sanctuaries take generations, from foundation to creation to living heritage. Even in times where hours pass faster than we scroll, the second doesn’t exist without the first.

Dust-laden rays continue their work, sprinkling sunshine on busts and models neatly positioned inside the garage. Some are recognizable as finished sculptures, others try-outs and sketches while others still are architectural scale models. A feather straightens its back two metres tall, another is held by a tiny pipe, and a hand points without fingers. There are postcards of places, goats and mirrored people, loved ones, lost ones and trails of thought. Covered or displayed. Remembered or forgotten, broken or complete. Tires and tubes, moulds of plaster and silicone thought up in wax, paper and paint, cared for and displayed. They are on the same wavelength as the car garage, the atelier and the monument. Hidden in plain sight alongside the ancient city wall and the bursting cherry tree.

From the garage we enter the office whose radio, once on, becomes its trusted companion. A tiny kitchen opens up into another part of the garage where a series of plinths with various heads line the wall. Parallel to the office, running back to the main space lies the workshop that holds tools and materials in place, measuring and making ready for lawnmowers and side tables, casts and cars.

At night the thin slender leaves turn black against the starry sky and the traffic slows down and leaves the space to the recurring soft but intense cry of territorial cats and glimmering trails of gravity defying brown snails on their quest to devour herbs.

From the garage out back we are invited into the garden. Once a wasteland, it is now a green dreamscape running from the garage on one end to the house on the other. A sanctuary for birds, cats, bees and mosquitoes, a curiously rich flora hosting some thirty different kinds of trees, a myriad of flowers, other plants and occasional herbs from the naturalized to the wild side of bugs and odd conversations.

We pick leaves of lemon balm, a lover of bees, and bring it to the kitchen where the Mother of Vinegars was fed wine some fifty years ago. The deep red brownish lump, the perfectly failed alcoholic has seen some cooking throughout the years. It has aged well in the big transparent glass jar on top of the little wooden shelf above the sink. It’s kept safe, still breathing among buttered bottles and glistening oils. Hot water brings lemon to a cup of tea in the garden.

To live is to continue, to be alive or have life. To be kept in a particular place. To breathe, sense and taste thyme, sun and the mosaic on the wall. Lean back into the pulse of a still life of ashtrays on the windowsill, sink into a yellow metal chair and take a drag of an assemblage of your own making, a pure nature morte with a mortar of lemon, squid and parsley and a frostbitten glass of rosé.

Baby basil

To rest is to (cause someone or something to) stop a particular activity or stop being active for a period of time in order to relax and get your strength back: to watch the sunset below the large leaves of a fig tree with the skin of its fruit beneath your nails and its juice on your tongue.

Living the image of his hat under a parasol, soft yellow and red tomatoes are cut, boiled, savoured and sent bopping among baby basil. On the grounds of delicate skin shed by a summer snake, ants organize meat from the previous night across the dusty patch below the breakfast table. Rocks resurface as sausages and line wooden boards. We place them as we rest on the steps to trim herbs while espressos rumble in the back.

To rest is also to lie or lean on something. On a chest, a folded towel or the breeze on the edge of a self-cleansing pool. To put something on something else so that its weight is supported: like a rugged stone holding a slim glass. To remain in a particular state or place and listen to nights filled with moons and stars, constellations above roaming collections of sounds that fill the trees after dark.

Warm polished wood

We exhale and come back to our tea on a stroll through the house where we gaze at trinkets and memories gathered through thousands everyday. It’s rare to be invited into decades of thought all at once. Her body is round and soft, one large piece of warm polished wood. Her head is an oval shoulder and her arms merge with her body and her legs become a wave that disappears in the tiled floor. We meet her on the way to the bathroom. She is solid and has aged well.

Pastis

Resistance is refusing to accept something, something that stops or makes progress slower, an attitude or action preventing flow. We have come to view resistance as a bump, an annoyance, like grass in the ski slope or unfamiliar opinions, things in need of elimination. Resistance is rather a skill, an art of continuous practice. Impatience sighs and looks for affirmative nods. Without resistance we would have destroyed the planet long ago. Resistance is to progress what air is to life. It is a force that asks for attention, persistence and care. It is seeing without getting blinded, tasting without swallowing, resisting a trillion for a tree and knowing when to run, when to walk and when to stop altogether.

In the garden, sculptures have crawled into place between Lawson cypress and copper beech in what once was a Beguine left in oblivion before it was discovered and cared for with curiosity and patient resilience. Art, baccarat and blackjack. Resistance is often powered by photosynthesis and pastis.

‘Work stops at sunset. Darkness falls over the building site.

1. Italo Calvino, The Baron in the Trees, trans. Archibald Colquhoun, Ana Goldstein (Boston, US: Mariner Books, 1977).

2. Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, trans. William Weaver (San Diego, US: Harcourt, 1974).

After Laenen died, his daughter and granddaughter managed his estate. They are currently engaged in the protection of the cultural heritage he left behind in Mechelen (and Provence), making it the place it is today. One aspect of the heritage are the works he left behind, the other is the private world behind them. For visitors and aspiring artists alike, it is a unique experience to encounter a place that opens up the artist’s inner world as it does in Mechelen. You are invited into his deep love for place and to see how it not only was present in his art, but also merged with his life through his garden and house. Like the acquired sculptural details he scattered about the garden, the large wooden sculpture by the bathroom or the creature in black mosaic executed directly on the living room wall. The following story is based on many nights in Mechelen coloured by Provence, in cause and effect by friendship, art and quarantine.

JPL

‘What he meant to say is not there, for he understood something else, something that was all-embracing, and he could not say it in words but only by living as he did.’1

Casts and cars

Early summer wipes the perspiring forehead of a casino, an awkward body towering on the outskirts of the city, on the fringe of branded nostalgia and Big Macs. We observe its striving outlook from a frituur across the street before we turn our backs on it and run our fingers by a lazy hinged steel gate whose fence has been swallowed by wild growing ivy and hops. Generations pass the ebb and flow of the deep-fried air as we open the gate and reach the entrance five steps in. Number 43, a light-blue faintly chipped wooden door in a car garage. Inquisitive pink roses guard the threshold and nip at our hair as we lean in to knock. They clearly question our intentions but let go as the door opens and we are greeted inside. Our host steps back, we step in and behold the scene that plays out inside as the years fall into place.

The space is engulfed in sun that streams past a tall hedge of rampant lush bamboo waving at us from the windows in the back. The narrow strips of light glide through the leaves, pass the glass as if one and the same, bounce off the walls and embrace the space in a soft yellow, primula kind of light. The old garage appears weightless in this state, perforated by rays that swallow the continuous sound of passing cars as we close the door. It’s been a long time. – Decades, nods the mechanic. He grabs a wrench from the wall in the adjacent room and enters the pit through a trapdoor. The garage eventually moved on to a man that years later leaned back in a large armchair as an artist and gave shape to the white sheet added a decade later by his daughter. She plugged in the radio when he left and scrubbed the walls in the company of her daughter. Sanctuaries take generations, from foundation to creation to living heritage. Even in times where hours pass faster than we scroll, the second doesn’t exist without the first.

Dust-laden rays continue their work, sprinkling sunshine on busts and models neatly positioned inside the garage. Some are recognizable as finished sculptures, others try-outs and sketches while others still are architectural scale models. A feather straightens its back two metres tall, another is held by a tiny pipe, and a hand points without fingers. There are postcards of places, goats and mirrored people, loved ones, lost ones and trails of thought. Covered or displayed. Remembered or forgotten, broken or complete. Tires and tubes, moulds of plaster and silicone thought up in wax, paper and paint, cared for and displayed. They are on the same wavelength as the car garage, the atelier and the monument. Hidden in plain sight alongside the ancient city wall and the bursting cherry tree.

From the garage we enter the office whose radio, once on, becomes its trusted companion. A tiny kitchen opens up into another part of the garage where a series of plinths with various heads line the wall. Parallel to the office, running back to the main space lies the workshop that holds tools and materials in place, measuring and making ready for lawnmowers and side tables, casts and cars.

Nature morte

At night the thin slender leaves turn black against the starry sky and the traffic slows down and leaves the space to the recurring soft but intense cry of territorial cats and glimmering trails of gravity defying brown snails on their quest to devour herbs.

From the garage out back we are invited into the garden. Once a wasteland, it is now a green dreamscape running from the garage on one end to the house on the other. A sanctuary for birds, cats, bees and mosquitoes, a curiously rich flora hosting some thirty different kinds of trees, a myriad of flowers, other plants and occasional herbs from the naturalized to the wild side of bugs and odd conversations.

We pick leaves of lemon balm, a lover of bees, and bring it to the kitchen where the Mother of Vinegars was fed wine some fifty years ago. The deep red brownish lump, the perfectly failed alcoholic has seen some cooking throughout the years. It has aged well in the big transparent glass jar on top of the little wooden shelf above the sink. It’s kept safe, still breathing among buttered bottles and glistening oils. Hot water brings lemon to a cup of tea in the garden.

To live is to continue, to be alive or have life. To be kept in a particular place. To breathe, sense and taste thyme, sun and the mosaic on the wall. Lean back into the pulse of a still life of ashtrays on the windowsill, sink into a yellow metal chair and take a drag of an assemblage of your own making, a pure nature morte with a mortar of lemon, squid and parsley and a frostbitten glass of rosé.

Baby basil

To rest is to (cause someone or something to) stop a particular activity or stop being active for a period of time in order to relax and get your strength back: to watch the sunset below the large leaves of a fig tree with the skin of its fruit beneath your nails and its juice on your tongue.

Living the image of his hat under a parasol, soft yellow and red tomatoes are cut, boiled, savoured and sent bopping among baby basil. On the grounds of delicate skin shed by a summer snake, ants organize meat from the previous night across the dusty patch below the breakfast table. Rocks resurface as sausages and line wooden boards. We place them as we rest on the steps to trim herbs while espressos rumble in the back.

To rest is also to lie or lean on something. On a chest, a folded towel or the breeze on the edge of a self-cleansing pool. To put something on something else so that its weight is supported: like a rugged stone holding a slim glass. To remain in a particular state or place and listen to nights filled with moons and stars, constellations above roaming collections of sounds that fill the trees after dark.

Warm polished wood

We exhale and come back to our tea on a stroll through the house where we gaze at trinkets and memories gathered through thousands everyday. It’s rare to be invited into decades of thought all at once. Her body is round and soft, one large piece of warm polished wood. Her head is an oval shoulder and her arms merge with her body and her legs become a wave that disappears in the tiled floor. We meet her on the way to the bathroom. She is solid and has aged well.

Pastis

Resistance is refusing to accept something, something that stops or makes progress slower, an attitude or action preventing flow. We have come to view resistance as a bump, an annoyance, like grass in the ski slope or unfamiliar opinions, things in need of elimination. Resistance is rather a skill, an art of continuous practice. Impatience sighs and looks for affirmative nods. Without resistance we would have destroyed the planet long ago. Resistance is to progress what air is to life. It is a force that asks for attention, persistence and care. It is seeing without getting blinded, tasting without swallowing, resisting a trillion for a tree and knowing when to run, when to walk and when to stop altogether.

In the garden, sculptures have crawled into place between Lawson cypress and copper beech in what once was a Beguine left in oblivion before it was discovered and cared for with curiosity and patient resilience. Art, baccarat and blackjack. Resistance is often powered by photosynthesis and pastis.

‘Work stops at sunset. Darkness falls over the building site.

The sky is filled with stars. “There is the blueprint”, they say.’2

1. Italo Calvino, The Baron in the Trees, trans. Archibald Colquhoun, Ana Goldstein (Boston, US: Mariner Books, 1977).

2. Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, trans. William Weaver (San Diego, US: Harcourt, 1974).

The political works

In collaboration with photographer Kristien Daem, we have assembled a series of works spanning different periods of Laenen’s practice. These works essentially arose from of a sense of distress, a personal urge, and gutteral reaction to the news reports and international events that took place during the artist’s lifetime. While they largely remained studio works and part of the artist’s personal realm until the day of his death, they are an important part of his practice. This is the first time they will be given a public platform.

In collaboration with photographer Kristien Daem, we have assembled a series of works spanning different periods of Laenen’s practice. These works essentially arose from of a sense of distress, a personal urge, and gutteral reaction to the news reports and international events that took place during the artist’s lifetime. While they largely remained studio works and part of the artist’s personal realm until the day of his death, they are an important part of his practice. This is the first time they will be given a public platform.

Part of Laenen’s early works, Le Disparu or De Vermiste, is a memorial to the Jewish deportations which is tightly connected to a childhood memory of the sound of passing trains coming through his bedroom window, trains departing from the nearby Kazerne Dossin in Mechelen/ Malines.

Jean-Paul Laenen, Le Disparu - De Vermiste, 1957, bronze and steel, 48 x 22 x 20 cm. Photography ©Dries Van den Brande

This series of over 20 drawings titled La Polonaise was an immediate reaction to the political unrest in Poland. On December 13th, 1981, Martial law was introduced in Poland, restricting the everyday life of the Polish citizens and leading to political imprisonment and numerous deaths of opposition activists. The repitition of a female figure - outstreched neck, releasing a primal scream - moves between rage, desperation, defeat, and terror.

These drawings eventually led to a sculpture carrying the same title.

Jean-Paul Laenen, La Polonaise, December 1981, ink on paper. Photography ©Kristien Daem

Originally intended for bronze, La Polonaise, 1982, remained in its raw state: a plaster cast fixed on a steel structure with a wooden base. A torn figure, arm outstreched in thin air.

Jean-Paul Laenen, La Polonaise, 1982, plaster, steel, wood. Photography ©Dries Van den Brande

This series of drawings was kept as a personal diary during the Kosovo War, based on daily news reports and drawn on leftover paper.

Jean-Paul Laenen, Untitled, c. 1999, ink and pastel on paper, 17,8 x 10,8 cm, series of 35 drawings. Photography ©Kristien Daem

Kosovo: Parce que is the only sketch of the ‘Kosovo’ series that was realised as a large scale pastel with different stages of the sketch and the source image still visible in the margins.

Jean-Paul Laenen, Kosovo: Parce que, 1999, pastel on paper, 106 x 79 cm. Photography ©Kristien Daem

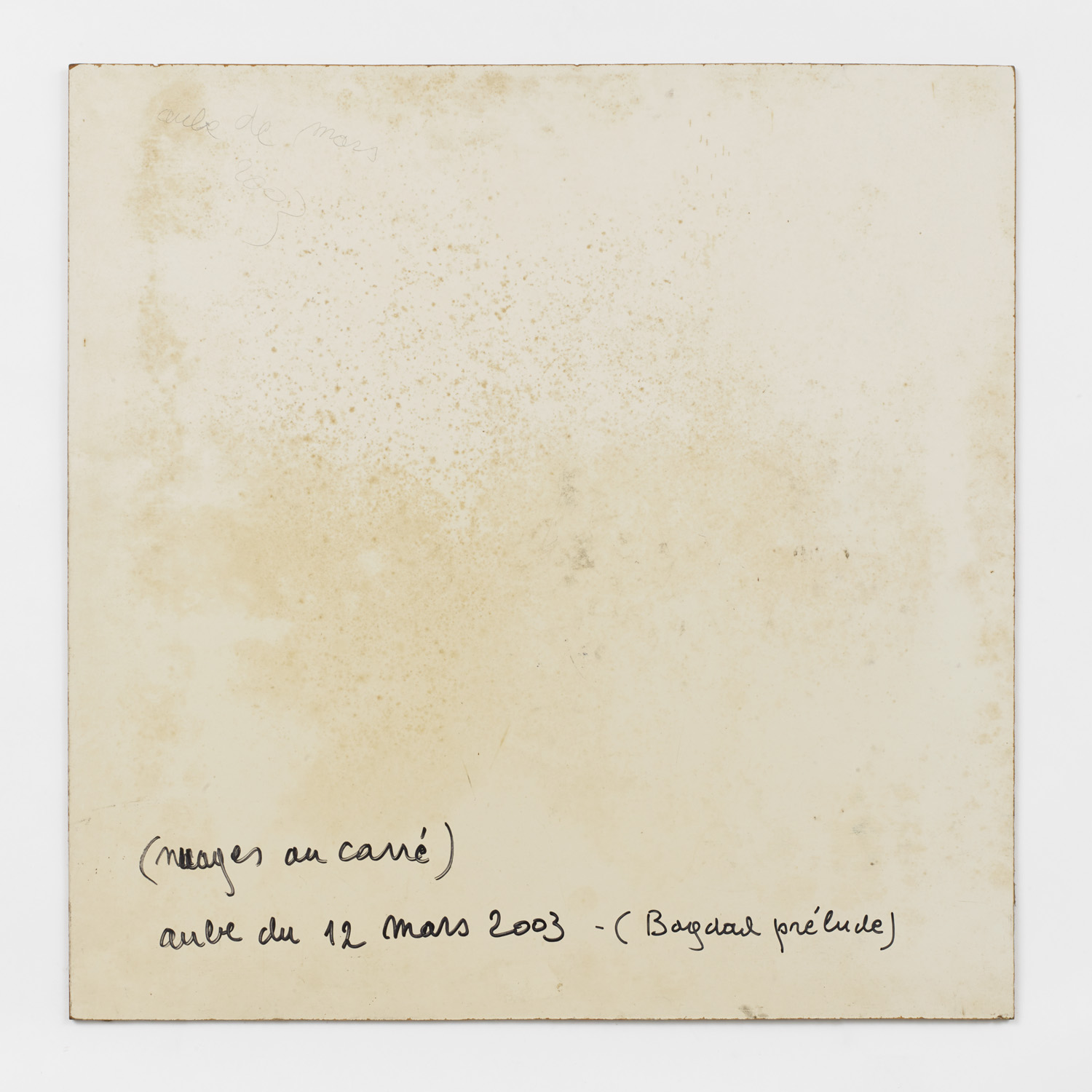

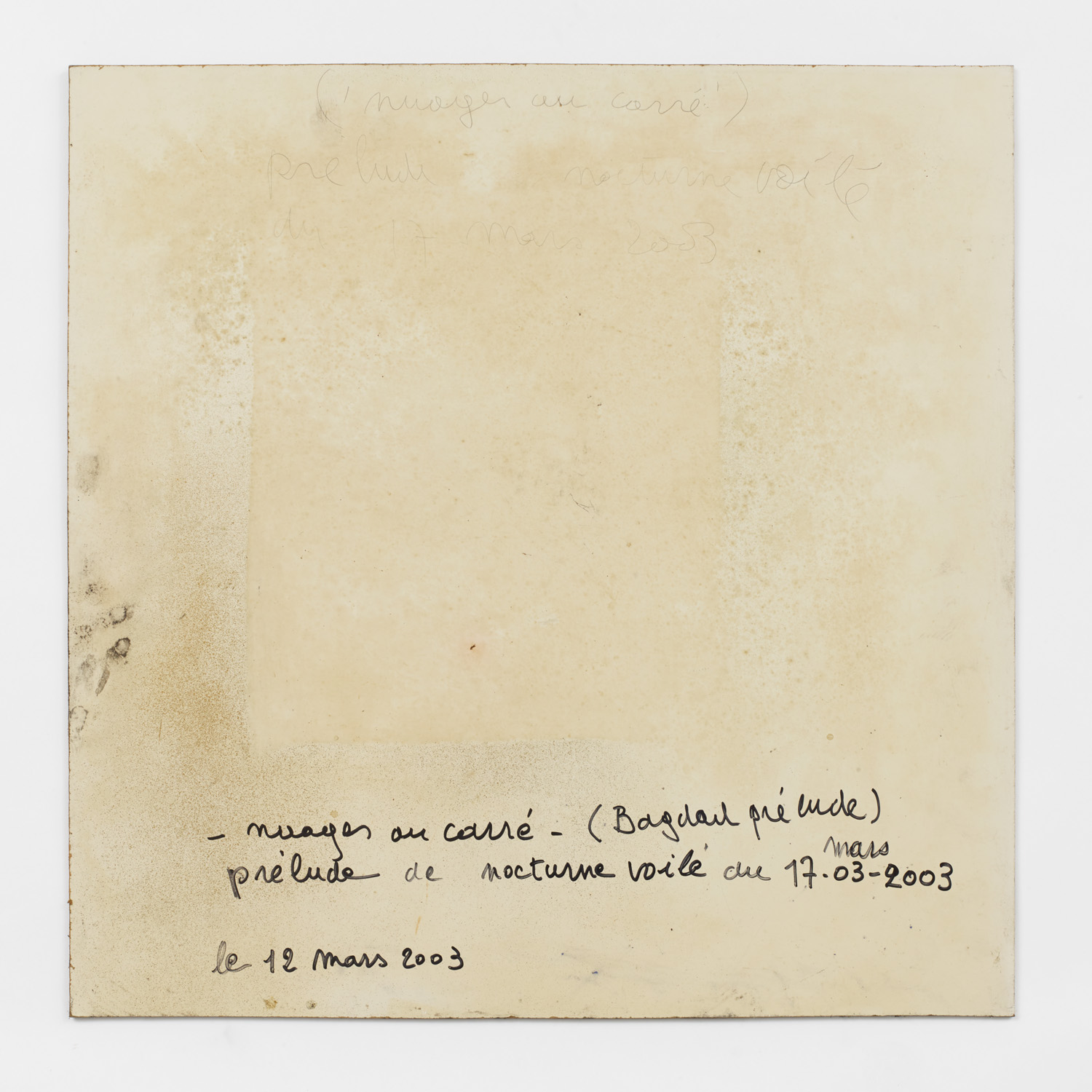

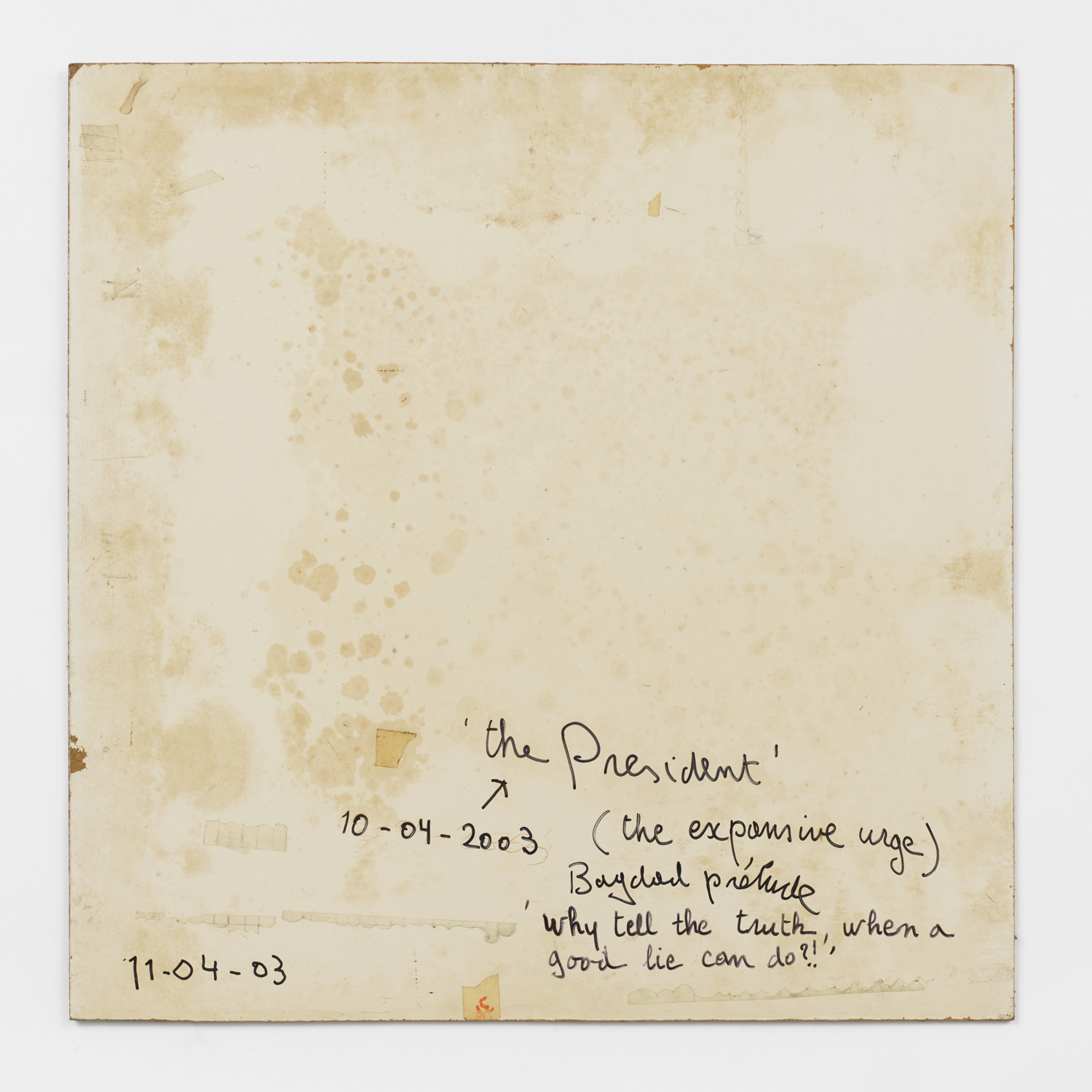

In the spring of 2003 Laenen made the ‘C.’ series, a series of 6 panels based on the military invasion of Baghdad and the international politics surrounding it. While the first half of this series remains an abstraction, predominantly focusing the increasingly threatening nocturnal skies of a besieged city, the military and political realm move to foreground in the second part of the series, making way for tanks, presidents, and confused territorial maps.

Jean-Paul Laenen, C. 1: (Nuages au Carré ) Aube du 12 Mars 2003 (Bagdad Prélude), March 2003, pastel on panel, 50 x 50 cm. Photography ©Kristien Daem

Jean-Paul Laenen, C. 2: Nuages au Carré (Bagdad Prélude) [prélude de nocturne voilé du 17-03-2003], 12 March 2003, pastel on panel, 50 x 50 cm. Photography ©Kristien Daem

Jean-Paul Laenen, C. 3: Le Feu du Ciel (Bagdad Prélude), 2003, pastel on panel, 50 x 50 cm. Photography ©Kristien Daem

Jean-Paul Laenen, C. 4: Les Yeux de la Nuit (Bagdad Prélude), March 2003, pastel on panel, 50 x 50 cm. Photography ©Kristien Daem

Jean-Paul Laenen, C. 5: ‘The President’, 10-04-2003 (The Expansive Urge) [Bagdad Prélude, ‘Why tell the truth, when a good lie can do?!’], 11 April 2003, pastel on panel, 50 x 50 cm. Photography ©Kristien Daem

Jean-Paul Laenen, C. 6: The Expansive Urge, April 2003, pastel and bister on panel, 50 x 50 cm. Photography ©Kristien Daem

Five years after Kosovo: Parce que, a sequel titled Beslan: Parce que recounts the terrorist attack and school siege in North Ossetia during which Chechen rebels took over a 1000 hostages, many of them children. The siege lasted three days and was eventually ended by a Russian operation, resulting in about 330 deaths. As the title suggest, a senseless perpetuum previals.

Jean-Paul Laenen, Beslan: Parce que, 2004, pastel on paper, 106 x 79 cm. Photography ©Kristien Daem

Laenen’s last unfished work is a sketch executed just days before his death in 2012. The pietà of Jemen, based on Samuel Aranda’s photograph for The New York Times which was awarded the World Press Photo 2011.

Jean-Paul Laenen, Untitled [Pietà Burka], 2012 (unfinished), pencil on paper, 110 x 75 cm. Photography ©Kristien Daem